AquiPor is honored to be ranked among the top 5 emerging stormwater management startups globally in a recent report put out by StartUs Insights. We take great pride in the solutions that we’re developing with an eye toward solving stormwater issues on a grand scale and a ranking like this validates our work to this point.

In fairness to other emerging companies in the space, this list is far from exhaustive as there are a number of companies developing promising technologies that look to have a major role in stormwater infrastructure in the future. Ultimately, it is an encouraging sign to see the trajectory of innovation in a space that has been known to be devoid of it in the past.

At AquiPor we believe that stormwater and urban flooding issues can be solved within the confines of the existing urban environment in cities. As we continue to develop our permeable hardscape material and integrated engineering technologies, we believe that large scale green infrastructure will finally be possible within the existing built environment.

The best is yet to come.

At AquiPor, we believe that the bigger the challenge, the bigger the opportunity. Suffice to say, the enormous water challenges that our cities face today represent even bigger opportunities for AquiPor to make our mark. After five long years of ceaseless R&D, we’ve finally arrived at a technology that we believe can be paradigm shifting in urban stormwater management.

For those of you that have invested, you have invested in much more than just a new construction product for backyard patios. We are developing our material technology to be the future of on-site stormwater management in cities. In the future, this material could be used in engineered stormwater designs that we haven’t even thought of yet!

What makes AquiPor material different is the pore size. We use a completely novel chemical technology approach to get material that is strong and permeable, but which features sub-micron porosity. It is capable of filtering out dirt, debris, and particle pollutants that are known to compromise existing permeable pavements.

For cities and developers, this means a small footprint, low-maintenance permeable surface design capable of managing stormwater runoff naturally, right within existing corridors.

As you can probably imagine, there are a lot of urban street miles in the U.S. So to be able to supply the market, we’ve been diligently lining up our supply chain and future manufacturing plans. We are working on some exciting developments to that end, which I’ll be sure to announce when I can.

In the end, big things are possible with the right combination of vision, technology, people, and capital, and your support at the outset of this launch has been incredible. Keep sharing our story and spread the word. We’re extremely thankful for that!

We've put together a short video to explain "The AquiPor Difference" and hope you'll stay tuned to our page for further updates. In the meantime, don’t hesitate to reach out with questions. Onward!

Severe weather in the U.S. takes a hefty economic and societal toll each year. In 2019 alone, at the time of this writing, there have been 10 weather events that each resulted in losses greater than $1 Billion. Of these, 3 included severe floods and 5 included “severe storm events”.

When I think of flooding, extreme images of Houston, New Orleans, and Tohoku readily come to mind. But urban flooding in U.S. cities happens far more commonly than the mainstream news storm event, and they cumulatively take a bigger economic toll.

More recent scenes like these in New York or Spokane don’t get national attention because they’re local and not quite “natural disasters”. But flooding events like these happen more often than you’d think and they go mostly unnoticed…save for the local residents that end up dealing with the damage.

A changing climate is making these events more frequent, but it doesn’t help that our cities are caked in impervious concrete and asphalt. Up to 40 percent of U.S. cities are covered by impervious surfaces in the form of roads, parking lots, sidewalks, and other pavements. Rain and melted snow that would naturally soak back into the earth and feed a normal hydrologic cycle instead turns into high volume stormwater runoff. That polluted runoff is channeled to wherever the grade was designed to take it, usually far away from where it originally fell.

Under normal conditions, stormwater runoff goes to a treatment plant to be cleaned before it’s discharged into our water systems. But more, a city’s downstream infrastructure gets completely overwhelmed by the sheer volume of runoff. The result is polluted discharge spewing into our rivers or up through manholes and into the street.

Better Stormwater Management

Stormwater management is the policy, planning, engineering, implementation, and maintenance of urban water systems and it is critical for the sustainability of clean water in cities. The classic approach to stormwater management entails channeling water away from impervious surfaces and the structures built atop them. We’ve constructed our cities on the assumption that the water that would have been absorbed back into the land can be transported away instead.

The problem is that the policies and the engineering that support an urban stormwater management plan is conceived within the expectations of past norms. But with weather events becoming much more unpredictable and urbanization adding thousands of miles of impervious surface area to our cities every year, designing stormwater systems with data from even five years ago is infeasible and dangerous.

Unpaving the Way?

Many urban planners point to impervious surfaces as the problem. Cities like Baltimore have even begun removing thousands of acres of pavement.

But pavement reduction as the sole cure for urban flooding isn’t scalable. Urban development continues to increase and pavements (roads, sidewalks, etc.) play a critical role in the transportation of people and goods, amongst other things.

Mimicking rural hydrology with green space is smart, but it is also limited by scale. Usable space in dense urban areas comes at a premium because there simply isn’t much of it. It’s why some cities questionably allow developers to build on flood plains and many other cities struggle with urban sprawl. There simply isn’t an endless supply of land area for stormwater parks, rain gardens, and vegetated swales. And where there is available space, it’s undoubtedly expensive. No question green infrastructure has a role to play in stormwater management, along with improving grey infrastructure. But to solve this issue at any meaningful scale, we need a whole new toolkit altogether.

The Future of Hardscape Infrastructure

If urban flooding can be tied to cities having too much impervious surface area and not enough green space, we can determine the huge role that permeable pavement will have in the future of urban infrastructure. Permeable pavement theoretically provides the function of normal pavement, while also playing the role of “green space” by allowing water to soak through it and into the ground below. But current market technologies are limited by their material capabilities.

Nevertheless, innovation is relentless. And it is usually driven by need. $103 Billion need Today there are cement and material technology startups developing the material of the future for on-site stormwater management. By creating permeable hardscape material that is extremely strong, with the ability to filter out contaminants in stormwater, cities will have the ability to greatly mitigate urban flooding and “future proof” themselves in ways that are actually scalable and practical. The ability of hardscape material is evolving, and it holds the key to sustainable water infrastructure in our cities.

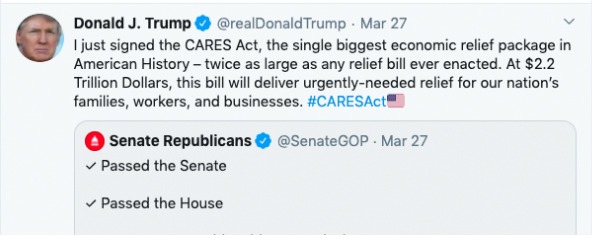

The Yuge CARES Act Stimulus Bill earmarks almost $500 Billion for large corporations.

Just like that, the most expensive stimulus measure ever taken was signed into action. As individuals and small businesses wait for the crumbs, corporate lobbyists are lined up at the $2.2 Trillion feed trough to help “save their industries”.

It’s hard to imagine how another round of huge corporate bailouts will jumpstart the economy. If we’re to recover from this, it will start with rebuilding durable national assets and creating new jobs doing it. That’s not going to happen by bailing out the airline industry. It’s going to happen at the local level with smart infrastructure investment.

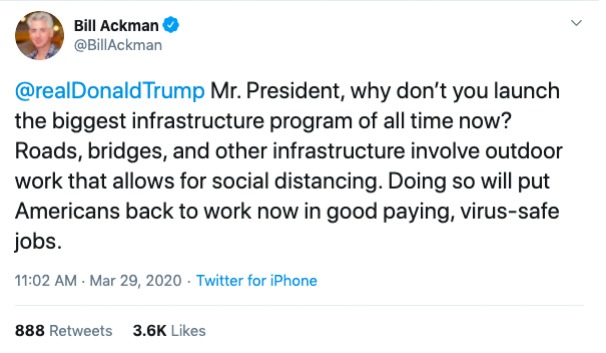

At least one billionaire hedge fund manager agrees.

Often taken for granted, physical infrastructure assets are crucial for a well-functioning society.

As this crisis has unfolded over the past couple weeks, it’s made me notice just how valuable local infrastructure is and the role that local governments play in making sure it functions. Municipalities provide the services, resources and infrastructure to keep communities safe. Uninterrupted water, sanitation, and emergency services are nothing short of modern miracles.

They are also an afterthought for federal funds, even as cities risk going broke.On the heels of this pandemic “shock”, it’s pretty obvious the U.S. needs to get serious about better preparing our cities for imminent surprises. Whether it’s a virus or Hurricane Katrina, the U.S. ought to get familiar with future-proofing: the process of anticipating the future through the development and application of methods that can minimize the stresses of future events.

More storms are coming: Whether it’s a novel virus or a hurricane, the U.S. needs to take the concept of “future-proofing” very seriously.

And what better way to do this than to begin investing immediately in the improvement of dilapidated and outdated U.S. infrastructure assets. The back-and-forth about infrastructure has been going on for so long in our nation’s capital that it has become a running joke. What’s not funny though is reading a D+ on America’s Infrastructure Report Card.

The group that puts out this Infrastructure Report Card report is the American Society of Civil Engineers. They estimate that the U.S. is on track to invest only half of what is needed in infrastructure over the next decade.

Even in normal times infrastructure investment should be a key component of any fiscal stimulus plan. It’s reported that a $250 billion annual investment in infrastructure could create 3 million new jobs in the first year alone. A package stretched out over ten years not only provides immediate economic stimulus, but also a solid foundation for further economic development down the road. A comprehensive, equitable, and climate-smart package that improves job quality and fixes broken assets is a no-brainer.

Treasury yields are below 1% making federal borrowing the cheapest it’s ever been. So get to it Washington. The challenges that we face in the 21st century can be solved. But not with the same path-dependence and risk-aversion that got us in this mess.

Quiet as kept, we are facing a water crisis in the U.S. that’s being inflamed by a serious innovation deficit in water infrastructure. It can be solved, but only through the intersection of new technologies and fresh approaches with status-quo establishments in the water sector. Easier said than done, but what a huge opportunity.

All things considered, urban water management sits low on the “environmental urgency” totem pole. A dangerous combination of institutional risk-aversion, paltry investment in new technology, and artificially low water prices factor into this lethargy. Meanwhile, urbanization, the decay of century old infrastructure, and unpredictable weather patterns are straining urban water systems to the brink of failure.

The Key to Climate Resiliency: Innovation

It used to be that we could rely on past data to determine groundwater supplies or the potential for flooding in a given area. Those days are long gone. A changing climate is a present reality that has everything to do with our future water security. In 2017, extreme weather cost the U.S. $300 billion.

New scientific research shows that ten times more Americans are at risk of being flooded out by rivers within the next 20 years, even if greenhouse emissions are completely and immediately curbed. If water security comes down to how cities address this new normal, old path-dependent approaches will prove disastrous.

Knowing that current water infrastructure in the U.S. is nearing the end of its useful life, utilities are hurtling toward $700 Billion in new spending on water projects. This is an unprecedented opportunity for new approaches to be adopted by the industry. Fortunately, paradigm-shifting technologies are being (and have been) developed in each cog of the urban water cycle.

Bold new material technologies in permeable paving for stormwater infrastructure, distributed water technologies, potable water reuse, and energy recovery from wastewater all show tremendous promise. These could be game-changers at scale, improving the physical structure and financial future for urban water systems…If given the chance.

Financing the Future of Water:

Institutional path-dependence is but one barrier for promising technologies. The other obvious barrier is the lack of private investment in the development and deployment these technologies. In a vicious circle, the industry that most needs new technologies repels the industry that invests in new technologies — venture capital. Herd mentality on top of herd mentality.

Normally, promising startups turn to venture capital to finance growth. But in a dislocated (albeit, huge) industry with slow sales cycles and regulatory sluggishness, it turns out that venture capital is inherently at odds with water startups. Ironically, this probably bodes well for startups in the space. While institutional investors play follow the leader and pile into more marketable environmental plays, innovative water technologies will be backed by new financing mechanisms that allow them to be developed, launched, and deployed in ways that can be truly impactful.

It is my feeling that we are entering a truly disruptive period in water infrastructure. Regulatory policy-making is getting lapped by technological advances and new startup financing mechanisms like equity crowdfunding are finding their footing. The truth is, real innovation finds its way around entrance barriers. And when outdated institutional factors influence decision making — even when a new technology demonstrates the massive potential to improve an existing issue — disruption looms. Recall, we all used to hail taxi cabs.

From nuisance floods to severe storms, most communities aren’t at all prepared for extreme weather. The climate is changing. It’s absurd to politicize it, because the climate always has been and always will be changing and humans can’t control it. Not even Al Gore-type humans. But with the vast majority of 7.5 billion humans living in cities that depend on centralized water infrastructure, the effects of extreme weather can be devastating.

Climate resilience was a fancy buzz-phrase ten years ago. It actually means something today, as 2019 marked the fifth consecutive year that the U.S. endured 10 or more extreme weather events causing greater than $1 Billion in damage each. And while the storm events that cause the most damage are newsworthy, we rarely hear about the smaller events that are occuring much more commonly. Smaller scale flooding is happening all the time in cities across the country, causing property damage and threatening the security of urban water systems.

Stormwater management is the policy, planning, engineering, implementation, and maintenance of urban water systems. It is a critical component of any city’s water infrastructure. But since these systems are conceived within the limits of expected behavior, it should come as no surprise that they are continually overwhelmed by larger storm events. From New York to Minnesota, a common theme endures: in the face of extreme weather, our nation’s stormwater infrastructure is failing.

Communities across the U.S. are responding on very different ends of the spectrum. In some cases, towns are trying to buy out flood-prone neighborhoods and turn them into wetlands. On the other end of the spectrum, officials keep their heads in the sand and do nothing. The majority of U.S. cities, however, recognize serious vulnerabilities within current infrastructure. Unfortunately, upgrading mammoth assemblages of underground plumbing and conveyance isn’t cheap, and a one-size-fits-all approach to stormwater management isn’t practical.

Remember how I mentioned that existing stormwater infrastructure in this country was conceived within the limits of what used to be expected? Federal rainfall estimates are continually being adjusted upward. As an example, a 100-year storm event in Minnesota, over the course of 24 hours, used to produce 6 inches of rain. Today that same storm is expected to produce 8 inches. In Austin, a 24 hour, 100-year rainfall event has increased by an average of 3 inches, and in Houston it’s increased by 5 inches!

Cities that commit to an evolving stormwater design philosophy will be most prepared for this type of sudden weather event. A shift from grey infrastructure - the pipes and conveyance system that moves runoff someplace else - to a more natural approach that manages stormwater right where it falls, will be critical to the future resilience of urban water systems.