AquiFlow is a proprietary aggregate that AquiPor has developed for use as an additive to concrete. Unlike other concrete ingredients, AquiFlow has some unique properties that make it a revolutionary change in concrete production. It allows concrete to act as a water filter - a porous material that can mitigate the effects of stormwater flooding and pollution, without a reduction in compressive strength.

This is huge for the industry. Concrete is the second most used substance on earth behind water, and is estimated to produce 8% of the total carbon footprint in the world. AquiFlow aggregate is a near net-zero additive, so replacing traditional ingredients with AquiFlow reduces that footprint, while simultaneously creating a porous, stronger than regular concrete and more climate resilient product.

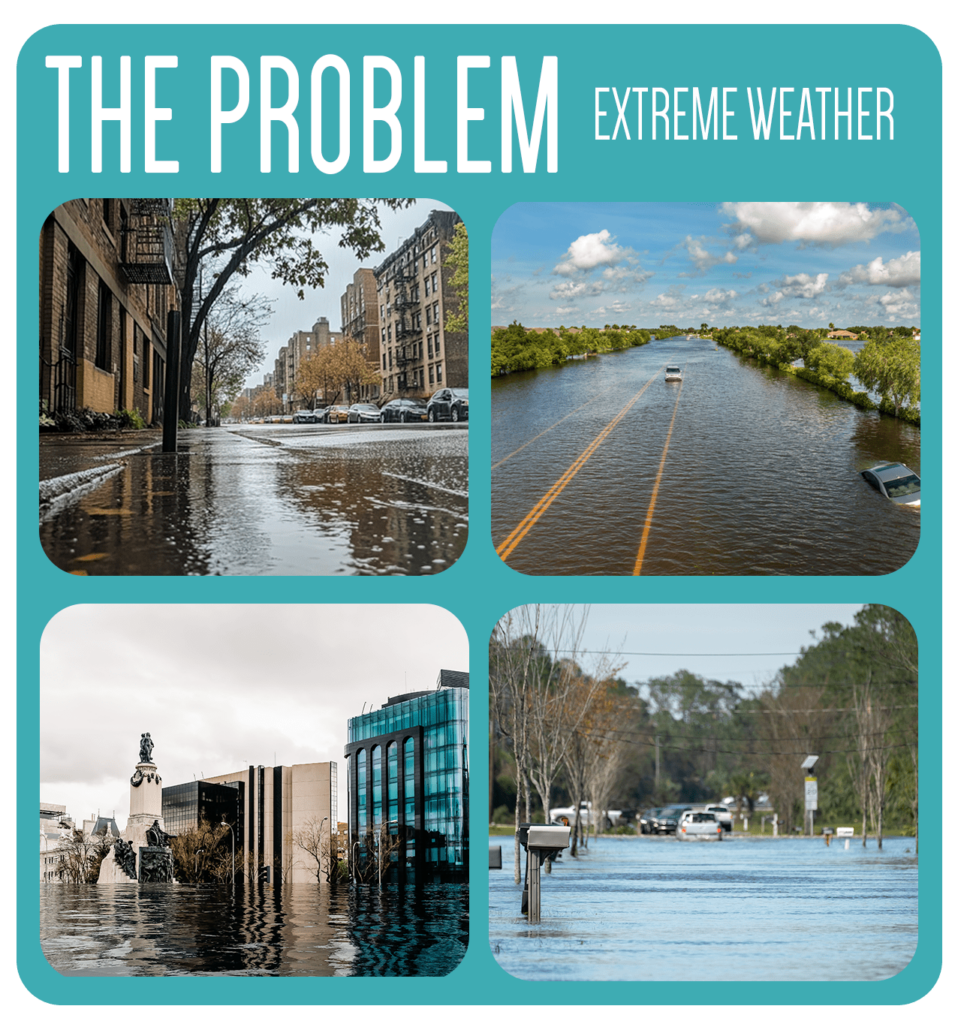

Not only is AquiFlow all these things, it replaces other less effective concrete aggregates that are more expensive, do less, and are becoming harder to find. AquiPor’s tech will eventually reduce costs, be more eco-friendly AND help stop stormwater flooding and pollution that is only increasing as the climate changes and extreme weather continues to increase in size and scope.

This is why AquiPor Technologies is so rare in the world of material technologies. It checks off two huge needs of a multi-billion dollar industry by being eco-friendly and easily accessible and adoptable to the industry as it is right now.

Concrete hasn’t changed much since the times of the Romans, but we believe we have Concrete 2.0, and like all other inventions that shifted the paradigm, it just needs a spark to ignite the world over.

We need your help to build the capacity to create, install, test and sell this truly remarkable technology. Which is why we have a crowdfunding campaign with our partners at StartEngine, allowing everyday investors like you to become a part of a revolutionary technology for one of the biggest industries in the world.

While so-called climate experts wring their hands about fossil fuel vs. EV powered vehicles, it turns out that the biggest climate threat from vehicles comes from their tires.

According to a recent report, 78% percent of the microplastics in oceans come from synthetic tire rubber, all by way of stormwater runoff. Those microplastics end up in marine life, and ultimately end up in the seafood that humans consume.

Tire rubber contains more than 400 chemicals and compounds, many of them carcinogenic, and research is only beginning to show how widespread the problems from tire dust may be.

“Tire wear particles” are emitted continually as vehicles travel and they range in size from visible pieces of rubber or plastic to microparticles. It is estimated that tires generate 6 million tons of particles a year, of which 200,000 tons end up in oceans.

The silver lining is that scientists studying the pollutants in stormwater runoff have found that green infrastructure solutions such as rain gardens could prevent more than 90 percent of tire particulates from entering our waterways.

AquiPor’s technology is being developed to accomplish the same thing, but at a much larger scale, by capturing and filtering runoff through our permeable system right within the urban landscape.

As we begin our water quality and filtration testing of our permeable concrete, we’ll keep you close to these developments!